#5 Ask Aishwarya: What to do when a student gets a spelling wrong even after it’s taught to her?

Question: I have repeatedly explained to this 8-year-old student how the spellings of ‘share’ and ‘people’ work. I explained why there is an <o> in ‘people’ and she has practised for about three weeks. She still writes it as *pepole. She writes ‘share’ as *shair or *shear. And ‘meter’ as ‘meater’ and ‘metar’. What should I do?

Firstly, let’s appreciate the fact that this teacher did what most teachers don’t. She didn’t provide any of the following inaccurate/unuseful explanations to the student:

Sound it out. (The student is desperately trying to sound it out and that is the issue.)

I don’t know. That’s how it is. (How does this help?)

Write it 5 times and you’ll remember. (If the student could remember spellings by writing 5 or 10 times, she wouldn’t be in an intervention.)

<o> is silent. (Yes, but why?)

<eo> is a digraph. (No, it’s not.)

The teacher has explained both in this moment and all the sessions leading up to this difficulty:

that graphemes can represent multiple phonemes

graphemes don’t always spell sounds

graphemes can show etymological relationships, i.e., they can function as etymological markers, at which times they are silent

the <o> in ‘people’ is an etymological marker that marks a relationship with the <o> in etymologically related words such as ‘population’ and ‘popular’.

The student still can’t remember the spelling. Why?

An important preliminary step is to think about the source of the error from the perspective of the student. What might have gone on in the student’s brain when she decided on a particular spelling?

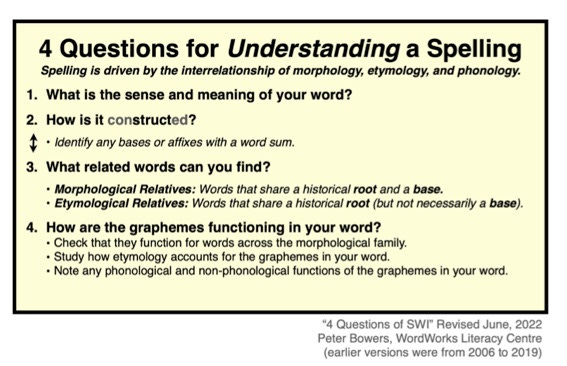

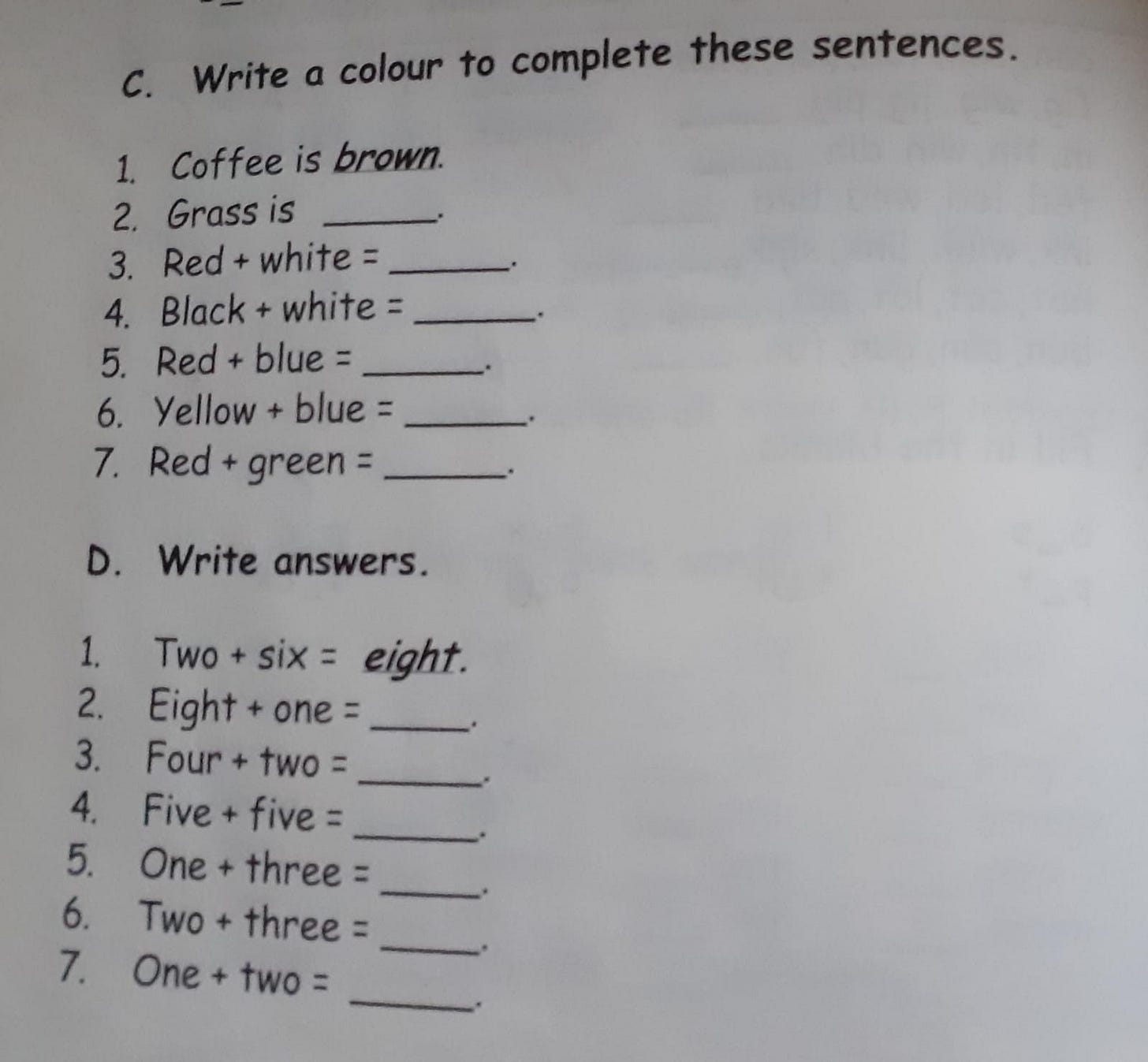

The misspellings of ‘share’ and ‘meter’ seem to indicate an overreliance or a sole reliance on phonology (“sound”). A useful starter activity that I use may be helpful here. I get students to repeat the following at the beginning of every class just like one would start with a prayer:

Everyone thinks that spelling is based only on sound. But it’s not!

Spelling is based on

meaning

structure

family and only

sound!

Source:

This kind of reinforcement is essential when the rest of the world goes out of the way to remind students to sound out words all day, every day.

In the case of ‘people’, the student clearly remembers that there’s an <o> in the spelling but is struggling to see the order of the letters. This is progress already: she hasn’t written *peeple for instance.

Also, understanding ≠ learning, assuming learning implies remembering.

As far as remembering is concerned, a sound (I mean well-grounded, not letter sounds) explanation of a word rooted in orthography is not very different from, say, a mnemonic. Intentional, well-designed practice and feedback; repeated opportunities for retrieval; and prevention or addressal of emotional barriers to learning are essential.

Let’s briefly look at each:

1. Well-designed practice and feedback

First and foremost, do not design the practice of isolated words. Always, always have the student practise in the context of word families.

For ‘share’ this would mean, writing the word sums while spelling them out. Depending on the situation, you can even include oral sentences to always keep focus on word meaning.

share

share + s → shares

share/ + ed → shared

share/ + ing → sharing

What if you have not taught the final <e> spelling rule yet? It’s probably time to. The student is already encountering/required to learn words with the final <e>. Even if you are not teaching the rule at this very moment, you can mention that the <e> is replaced (or eaten, as one of my cheeky students says) by the vowel suffix, and plan to teach the rule as soon as you can schedule it.

Let’s assume the student still writes ‘shear’. It’s a great opportunity to tell them that ‘shear’ is an entirely different word. Sharing your chocolate is different from shearing your chocolate, although doing the former may require you to do the latter.

Here are a few other things that may help:

comparing the pronunciation of ‘share’ and ‘shear’.

letting them know that *shair isn’t a word in English although you can see why they wrote it; it makes sense if English spelling was based only on phonology; it’s not

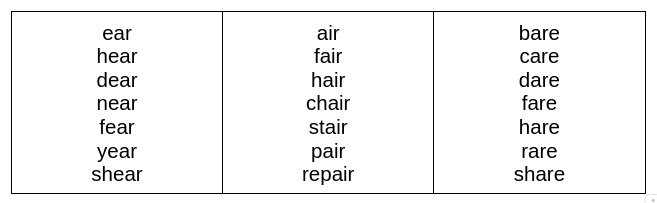

study the table below:

compare pronunciations across columns

study what the <e> does in words in the third column

For ‘people’, how do you help the child remember the order of letters?

Again, family to the rescue. The etymological family provides us with the opportunity to help with spelling recall and teach new words, both their spelling and meaning. In short, the student is not just struggling to remember one spelling for weeks but is engaging with new words and concepts that (incidentally) also help her to remember the tricky spelling.

So, teach the following words together with their meanings:

people

popular: known by a lot of people

population: the number of people in a place

This allows you to show not only that the ‘people’ has an <o>, but also this pattern, which you can’t observe unless you study the family.

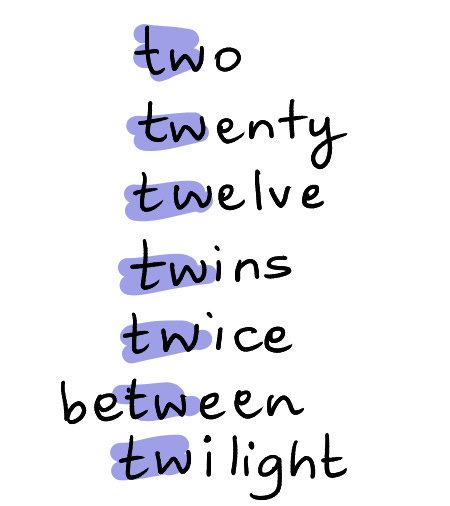

Keeping the <op> together is what shows that it’s a family. Just like the <w> in this one:

The mere presence of <w> is not enough to carry the historical relationship, the <w> has to be right after the <t>.

When the student writes *pepole, you could also tell her that there’s no such word in English. You can attempt to pronounce it and say, “Someone reading it may think it is [pɛpoʊl].

Allow the student the opportunity to engage with the error, to consciously and not so consciously absorb what might be happening and what should change. The time investment here is well worth it.

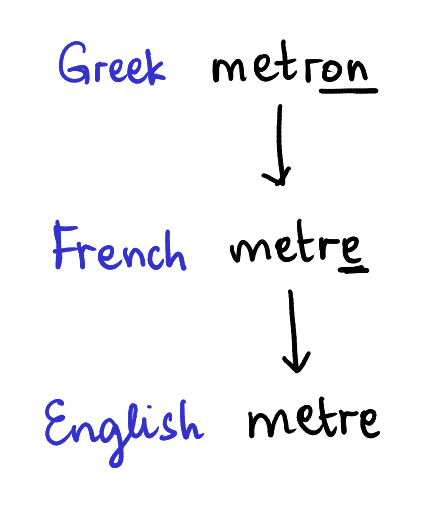

The misspellings of ‘meter’ also indicate how much more necessary it is to reinforce the fact that spelling is not based on sound alone. To help with this spelling, let’s first turn to etymology:

The more words you investigate, you will begin to realize how common the <-on> suffix is in Greek and how much French likes to insert the <e> at the end.

Let’s now look at a few members of the morphological family. You’d teach the student a few of these based on relevance and time.

metre

metre/ + ic → metric (Just this one word sum can reveal the spelling to the student; you don’t need any of the remaining morphology or etymology if you’re pressed for time.)

ge + o + metre/ + y → geometry

sym + metre/ + y → symmetry

Use the search pattern <metr> in Neil Ramsden’s Word Searcher to find more words in this family.

The word in the question, however, was ‘meter’, not ‘metre’. This is an American respelling of ‘metre’. It’s extremely useful for the student to know what happens with re/er, our/or, ise/ize, etc.

If you choose to use the American version, you can represent the word sum for ‘metric’ as <met(e)r + ic>.

As a general rule, when a student depends entirely on “sounds” (phonology), immediately bring their attention to meaning, morphology and etymology. In fact, I’d do it yesterday. This work is urgent. The more we hesitate to bring in meaning, morphology and etymology, the child will continue to learn to depend solely on phonology, a habit very hard to break especially when self-reinforced repeatedly.

2. Repeated opportunities for retrieval

Dictation is the most efficient retrieval method I know. But again, isolated dictation may be useful only some of the time. Say, I dictate ‘people’ with a bunch of 9 other random, unrelated words, and the student gets it wrong, it does two things:

It shows me that the student still hasn’t got the spelling, and will most likely get it wrong in a natural setting such as writing an answer or a paragraph in an essay.

The student encounters yet another failure: “Aargh! I just don’t get the spelling of ‘people’!”

I want to uncover (a) while not allowing (b) to happen. (See point 3 for more on this.) So, I give dictation in families for a while before I move on to including the word in a random, isolated list. So, although my aim is for the student to learn the spelling of ‘people’, I’d first dictate ‘popular’ and ‘population’ before I dictate ‘people’.

What if the student gets ‘popular’ and ‘population’ wrong? No sweat. Ensure they’ve got the <pop> part right, gently show the right spelling and move on. Your aim was to teach ‘people’ at the moment anyway.

When you have slightly more time to spare, I suggest you switch it up a bit and try methods other than dictation. Here are a few options:

What’s the <e> doing in ‘share’?

Give me examples of spellings that had an <re> ending that were changed to an <er> ending by the Americans.

What’s the <o> doing in <people>?

Oral odd one out: share, air, pair, hair.

Oral spellings

Phrase dictation

Sentence dictation

Fill in the blanks: ____ is your house? ____ you in Yeshwantpur yesterday?

Answering a question (such that the answer has the target word): Why should children not be forced to share their toys?

Fun quizzes with points

My favourite resource in this regard is Everyday English by Jane Sahi. It has tons of low-stress ways for spelling assessment and retrieval while keeping the student’s brain engaged and smiling. Here are a couple that I love:

Yes, you have to ensure that the answer to the first question is not available in the second.

Some parents and teachers ask me how many repetitions it should ideally take for a student to ‘get’ the spelling. If you want a “research-based” answer, read this, but beware, Shanahan loves phonics; I don’t. He talks about asking students to take a picture of the word with their eyes, etc. That’s a sure-shot recipe for errors like *pepole and is especially frustrating for students with learning disabilities. If they could take pictures with their eyes, they would have done it already <insert eyeroll>. The link is, however, a good starting point for you to find research papers to read on your own.

My answer to this is a question in return: How many times have you actually repeated it?

When an adult feels a spelling is simple, time stretches for them. Sometimes, when I have only provided 3-4 opportunities for retrieval, I begin to feel like it has been 30 times. My impatience plays tricks on my brain. A spelling that’s easy for me may be extremely tricky for a student. Sometimes we expect results before we’ve put in all the work.

After what feels like multiple, exhausting attempts to you, I suggest you ask the student: “Do you know why this spelling is tricky for you? My brain can’t seem to figure it out.”

Here’s a recent conversation that illustrates the usefulness of this question:

Me: You have spelt ‘umbrella’ as *umbralle. You have misspelt this word many times in the past. But you have now learned that there are 2 <l>s in the word, you are not skipping any syllable, and you are beginning the word with the correct vowel. Do you know what’s happening now?

11-year-old student: I just know that there’s an <e> and an <a> in ‘umbrella’ but can’t remember where is which.

Me: Ok, let’s look at your name, ‘Krutika’. The last <a> in your name is the same <a> you hear at the end of ‘umbrella’ or ‘sofa’. If <a> goes at the end, <e> should be in the second syllable, right?

Krutika has spelt ‘umbrella’ correctly ever since.

Given complete English words don’t end with <a>, it makes sense why this word had been giving her trouble. What seemed outwardly as a grave error of a very common, easy word might have just been Krutika’s unconscious observation of English spellings. The final <a> possibly made her uncomfortable and hence confused her.

I think the underlying anxiety in this question is, “Is my child normal? Why is she taking so long?” This is what I have said in response:

“Your child may or may not be “normal” or neurotypical. But I know for a fact that your child is wonderful, intelligent and curious and has a temporary issue with remembering a certain spelling. Explain the spelling using the 4 questions above and provide retrieval opportunities for 3 weeks, maybe during breakfast, lunch and dinner. Come back to me if they are still struggling.”

No, I’m not lying. All the students I have taught (99.99999%) have been wonderful, intelligent and curious. And yes, 3 times a day for 3 weeks is an unfailing prescription. It teaches the student the spelling while teaching the adult patience and the fact that their child can learn, and that there is nothing wrong with them.

Retrieval should always address 3 concerns:

Is the activity really allowing the student to access and reorganize long-term memory? If the student is looking at the words 5 minutes before your dictation, it’s a waste of time.

Is the activity only pointing to errors or giving the student the time, space and support she needs to understand her own misunderstanding or gaps in knowledge? Does it allow her to ask questions even if they are about things explicitly taught earlier? Will her questions be answered with patience and thoughtfulness even if it is the sixth time?

Does the retrieval leave her feeling energized or neutral, and not terrible for getting something wrong AGAIN?

This brings me to the last point.

3. Prevention or addressal of emotional barriers

I can give you four foolproof ways to make learning burdensome and torturous for a student, especially if they have a learning disability.

Teach them something they’re not ready for: expect the student to master the spellings of ‘January’ and ‘February’ when they are still figuring out shorter words such as ‘bat’, ‘with’ or ‘look’. A common practice for five and six-year-old students in most schools.

Ask them to guess or memorize when you don’t know an explanation: Why does ‘daughter’ have a <gh>?’ Because that’s how it is. (that’s a <ugh>, btw)

Directly or indirectly make them feel they’re not enough: give them tests they are going to fail, always make it about effort and attention, call them lazy and uninterested, make spelling errors their moral failings, compare them with siblings or other students

and the most ubiquitous, least talked about:

Hurry them: interrupt them, push them from school to dance class to chess class, ask them to eat fast, bathe fast, move fast, think fast.

Last week, a curious and eager-to-learn 7-year-old was told by her teacher to make her brain work faster. She asked me that evening, “How ma’am?”

My students tell me that writing in school, whether it’s copying from the board, taking dictation or writing on their own, never allows them to catch their breath. They need to be extremely fast if they must keep up. Otherwise, they lose their lunch breaks and evenings to more writing so they can complete their notes. The stress from incomplete work is worse.

For some, my class is the only space where someone waits for them to think through, organize their thoughts and arrive at something. It’s especially important for me, however difficult it is, not to hurry. It’s hard given I know how much the student is behind.

I give in to the impulse of pushing things along from to time. Sometimes a parent in an online class does that with their words or just their energy. It’s hard to wait when a student is thinking through something. Harder when they are thinking through something that appears to be basic or silly or something they must have already mastered by this age. Harder still if the concept was just taught to them yesterday.

From time to time, when a personal struggle or a health flare diminishes my patience, I ensure I go back and apologize to the student and remind them to let me know when I hurry them next. They never do. Over time I have realized that giving them permission to advocate for a less hurried learning space for themselves possibly tells them that I don’t intend to hurry, but still puts the responsibility on them. Imagine the cognitive load, self-awareness, vocabulary and self-advocacy skills I am demanding from 7 and 8-year-olds. Everything I can’t manage to do at 36 in lower-stakes situations even with family members.

I found a better solution in a post-it stuck on my laptop that reads ‘wait’. It’s always right in front of me so I learn and relearn patience every day.

Essentially, the effectiveness of any strategy, no matter how great or research-backed, is severely limited if the student’s self-image and self-worth are

harmed or

not nurtured, repaired and healed as necessary

in the process of teaching them reading and spelling.

TL;DR: Take care of the child’s heart first.

If your question now is, “Why should I bother learning, teaching and building orthographic knowledge when I can use tricks such as mnemonics as long as I get practice and retrieval right and take care of the emotional barriers?”

You can.

Except the student will not have the opportunity to develop a mental schema about how the language’s spelling system works. Therefore, she cannot use it to analyze and learn other spellings. A student who remembers the first four letters of ‘beautiful’ using the mnemonic ‘Big Elephants Are Ugly’ will have missed a beautiful opportunity to investigate the <eau> trigraph, its Frenchness, and will need newer mnemonics to remember words with the same trigraph such as ‘plateau’ and ‘bureau’.

She is also required to remember random, isolated mnemonics, thereby infinitely increasing her cognitive load with every new tricky spelling. But when a student understands the system, cognitive load progressively decreases because patterns repeat over and over again providing retrieval and relief at the same time. My teacher, Dr. Gina Cooke always reminds me: if dyslexic students were good at remembering isolated facts without the big picture (the system!), they’d never have trouble with spelling in the first place.

Investigating words and word families and seeing patterns and connections increase the student’s knowledge, critical thinking and confidence.

Schools routinely invest big money in unproven yet fancy-looking interventions to teach critical thinking and 21st-century skills while all along ignoring (even looking down upon) the opportunity to teach reading and spelling well. I’d go as far as to argue that teaching spelling while/by teaching about the spelling system isn’t even two birds (spelling and critical thinking) with one stone. This is the one bird (spelling) parents are paying schools for.

Thank you for being one of my readers; I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

Liking this post, so that others are encouraged to read it;

Leaving a comment;

Sharing this post by email, WhatsApp, or on social media;

Subscribing to this substack;

Currently, Substack is not supporting payments to many Indian writers including me. Click here to pay me directly via UPI or PayPal to access paid content.

Sponsoring my work with students who cannot afford to pay fees.